PretensT

Tensegrity is a special kind of structure made of push and pull.

Project maintained by elastic-interval Hosted on GitHub Pages — Theme by mattgraham

Tensegrity Violation!

In this project I’m setting out to commit a heinous violation of my tightly held tensegrity principles. I believe that there are certain foundational ideas in tensegrity structures, and one of them is that any element relationships which introduce shear, bending, or torque are forbidden.

That is not to say that you can’t just do it, but I argue that a crisp mathematical definition is best for establishing the category “tensegrity”. There’s more to be said about this, but I’ll save it for another post.

The violation in this project is for a noble cause: to illustrate a point and help me think through potential innovations which make building these structures easier. This tensegrity will exert a force which would tend to bend its struts.

Scaffolding

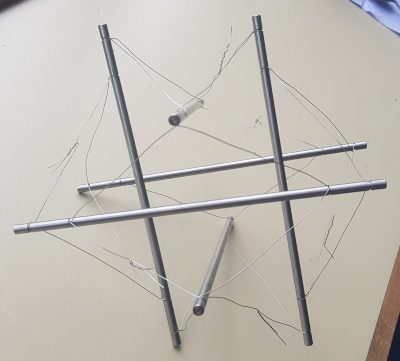

The basic structure is the same six-strut “brick” as last time, but this time I’m not interested in tightness or the separation of tension from compression.

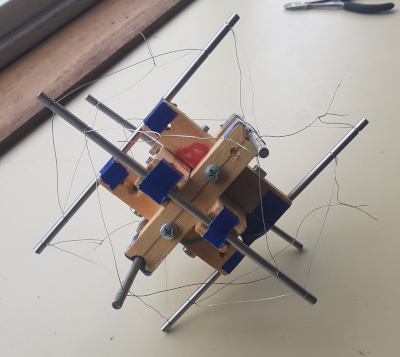

This will be a quick and dirty build, and I will use this nice “nucleus” scaffolding element that I once made with my friend Graham Smith at his “Harbour Hut” workshop across the river in Amsterdam (the Hut has since been bulldozed to make room for fancy homes).

The key feature of this scaffold is that it forms a temporary nucleus for holding the brick’s struts so we can worry about the tension, but more importantly that you can disassemble it later.

Prepare for Tension

With a little tape it was easy to prepare the compression in more or less the right positions, so that I could wrap tension around it.

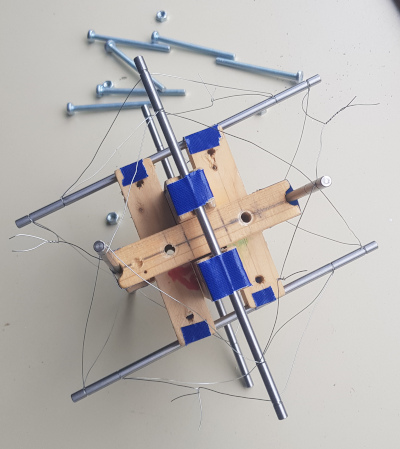

The struts I’m using were found many years ago in a surplus shop in Toronto (Active Surplus, back in the day), and they are probably the stainless steel axes of some kind of factory roller system, because they have precisely machined grooves at two positions near their ends.

It was these grooves that suggested this experiment to me, because each bar had 4 of them.

Wire Toy-Tension

I really took the easy way out for this model by using a stiff thin wire which I was able to wrap around the bars such that the wire settled comfortably in the existing grooves.

The amount of tension is not impressive at all, and you can see that the wires are not even particularly straight. But like I said, this time it’s not the point.

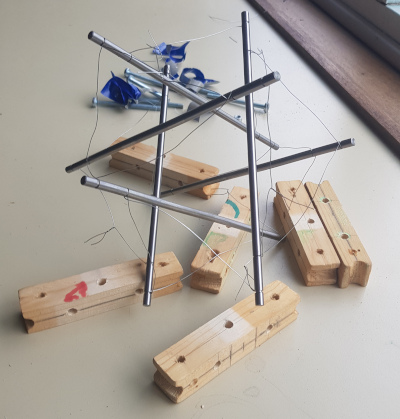

Dissolving the Nucleus

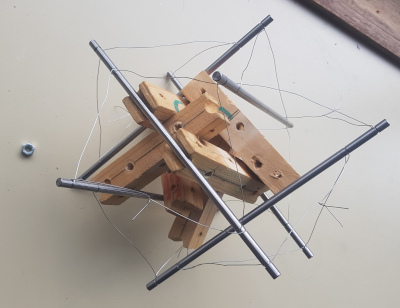

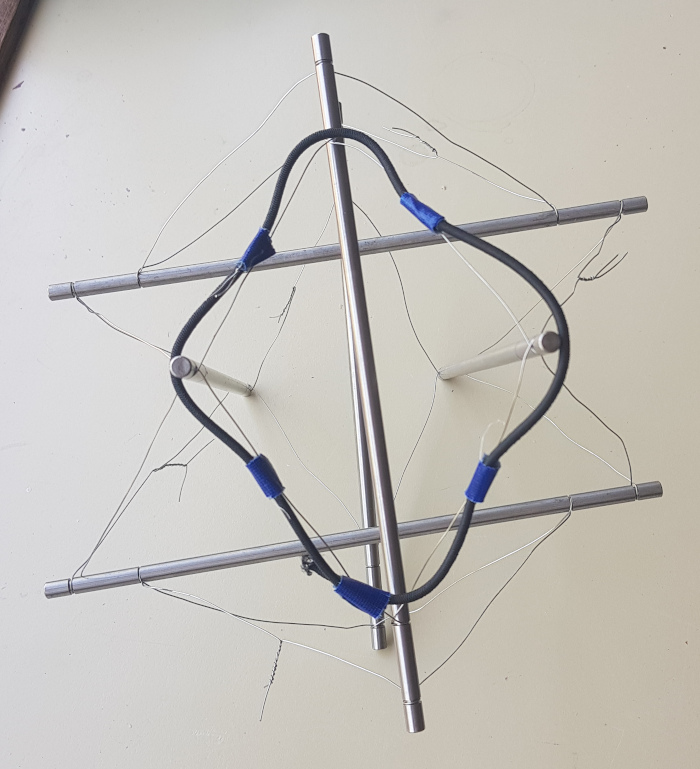

With the tension hooked up and more or less strong enough to hold things together, the next step is to remove the bolts holding the nucleus together.

With no bolts, the parts of the nucleus fall away like Jenga bricks.

What we are left with is six bars suspended within six diamond-shaped tension loops. The loops join the inner grooves to other outer grooves.

It’s not hard to imagine these connections being rigged to slide to different positions along the bar (rather than in grooves). I wonder how it would behave.

More clearly

Since it can be a little hard to pick out the way that the diamond tension is working here, I added a loop of cord to highlight the nearest one.

Conclusion

Displacing the joints into separate connections helps me think about about a potential optimization where there is a “diamond of tension” prepared together with each strut.

The diamonds can just as well be pre-measured while slack and later tensed when the whole is constructed and the struts lengthened, so that would achieve prefab tension.

My apologies for violating a fundamental tensegrity principle for illustrative purposes, but with the cheesy wire tension it should be clear that nobody is supposed to take this tensegrity seriously anyway.

Projects:

2024-07-23: "Bouncy Wooden Sphere": what you can do with a discarded bed2024-04-23: "Twisted Torque": tied into a permanent twist

2023-03-27: "Easy 30-Push Sphere": one simple element

2022-10-05: "Glass and LED": going big and colorful

2022-09-29: "Fascia": dancing with tensegrity

2022-08-30: "Mitosis": the four-three-two tensegrity

2022-08-04: "Push Bolts for the People": finalizing design and getting it out there

2022-06-22: "Head to Head Push Bolt": M5 and M6 bolts symbiosis

2022-05-30: "Hiding Knots": bump up the aesthetics

2022-05-25: "Innovation with 3D Printer": the push bolt

2021-12-02: "Headless Hug": breaking a rule for the sake of symmetry

2021-10-28: "Rebuilding the Halo": finally got it right

2021-10-20: "Convergence": growing and reconnecting

2021-07-27: "120-Strut Brass Bubble": taking the next step up in complexity

2021-05-26: "30-Strut Brass Bubble": bouncing spherical tensegrity

2021-04-08: "Bow Tie Tensegrity": better bend resistance

2021-03-29: "Six Twist Essential": what if more hands could see?!

2021-01-25: "Minimal Tensegrity": no more tension lines than absolutely necessary

2021-01-18: "Degrees of Freedom": first adjustable hybrid tensegrity

2021-01-11: "Fractal Experiment": a tensegrity of tensegrities

2020-12-09: "Axial Tension": pretensing what is already pretenst

2020-11-02: "Halo by Crane - Part 2": the strengthening

2020-10-26: "Halo by Crane - Part 1": assembly complete but strength lacking

2020-10-12: "Brass and Tulips": a tight and strong tensegrity tower

2020-08-10: "Prefab Tension Tower": the tower of eight twists

2020-07-27: "Elastic Bubble": building with elastic ease

2020-07-13: "The Twist Sisters": left-handed and right-handed

2020-07-06: "Radial Tension": Pulling towards the middle

2020-06-22: "Diamond of Tension": Four pulls for every push

2020-06-15: "Prefab Tension": Separating compression from tension